“Now, you’ll feel a little pinch,” says the nurse, as she draws a patient’s blood. Perhaps as soon as three to five years from now a simple blood sample can answer the complex question: “Do I have cancer?” or even “Do I still have cancer?” Seems like a medical miracle fairytale come true that a disease so confounding as cancer could be humbled by a simple needle prick. From so little may come so much—information. Boomers, take note: About 78% of cancers are diagnosed in people 55 years and older.

Partners in Progress

On Jan. 3, Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the largest hospital-based research program in the United States, announced a collaborative agreement with Veridex of Johnson & Johnson. It was a quiet announcement of sorts with possibilities capable of a strong ripple effect. The program seeks to establish a center of excellence in research on circulating tumor cell (CTC) technologies. The goal, says J&J, is to develop and commercialize novel technologies for capturing and characterizing CTCs, solid tumor cells found at extremely low levels in the bloodstream which may offer a key to noninvasive characterization of cancer and potentially to early detection.

The project seeks to bring to market an easier, more accurate test that will identify a lone cancer cell floating in the bloodstream and then capture it, even as it exists among a billion other normal cells.

Hope Springs Eternal

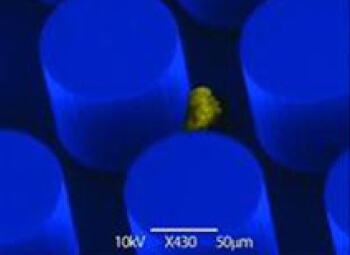

The “liquid biopsy” uses a microchip. As expected, some experts suggest the usual caution against being overly enthusiastic, reminding us that the process is still in early stages—even though one version of the chip was developed in 2007. Now the technology is “new and improved” thanks to MGH researchers including Dr. Daniel Haber, cancer genetics specialist and director of the hospital’s Cancer Center. Along with the approximately 1.5 million people expected to be diagnosed with cancer last year, he’s hopeful that the test may help circumvent unpleasant biopsy tissue samples and also scans in route to faster answers. Additionally, it could also answer that often-asked question: “Is this drug working for me?” If it isn’t, the ability to quickly alter treatment protocols could be life-saving.

In the uphill battle against cancer, this test can’t help but feel like “big news.” The National Institutes of Health tallied overall costs of cancer last year at nearly $274 million. That’s an astounding number that can’t begin to quantify the emotions of cancer patients and those who love them.